Thanks to the recent discovery of 90-year-old police files, unearthed by researchers at the National Archives in Kew, England, one can say with some confidence that -- in England, at least -- "modern" photographic surveillance began in September 1913. While it's true that Scotland Yard had been systematically photographing every single prison inmate incarcerated since 1871, these weren't true surveillance photographs because they were taken openly, at close range, and with the inmates' knowledge. But what Scotland Yard started doing at Holloway Prison in 1913 was something quite different, and uncannily similar to police and "intelligence gathering" practices that, today, have become both commonplace and technologically advanced: taking photographs covertly, from far away, and without the inmates' knowledge or consent. And this new regime of spying required that Scotland Yard buy some new, state-of-the-art equipment -- a Wigmore Model 2 reflex camera and an 11-inch-long Ross Telecentric lens -- and build and install a disguised location from which to take the pictures.

All this was necessary because a certain group of inmates (18 political activists who'd been imprisoned for the "violence" of their tactics) refused to have their pictures taken by prison authorities. Every time they saw someone trying to take photographs of them, these surveillance camera players would do something -- hide their faces, make "funny" faces, refuse to keep still -- to ruin the final product, to make it useless in identifying them. These extremists were called suffragettes, and they were women who demanded the right to vote and, after 25 years of very difficult fighting, finally won it.

Formed in 1903, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) created their first major scandal on 17 January 1908, when a group of suffragettes chained themselves to the railings of 10 Downing Street and were subsequently arrested. Four years later, the suffragettes started a campaign of window smashing, which not only targeted 10 Downing but also over 250 buildings (!) in London's posh West End. Several suffragettes were arrested. "Window-breaking, when Englishmen do it, is regarded as an honest expression of political opinion," Christabel Pankhurst wrote in her memoirs. "[But] window-breaking, when Englishwomen do it, is treated as a crime."

In September 1913, the British Home Office gave its approval and provided the necessary funds for prison officials at Holloway Prison to start using covert tactics (secret surveillance) to photograph the suffragettes as they walked about the prison's exercise yard. The plan was, after the women were released from prison, to distribute copies of their photographs to the agents assigned to follow and keep tabs on them, and to the guards stationed at places the suffragettes had already attacked or seemed likely to attack in the future. For each suffragette, the police created a file containing photographs, physical descriptions, and surveillance reports.

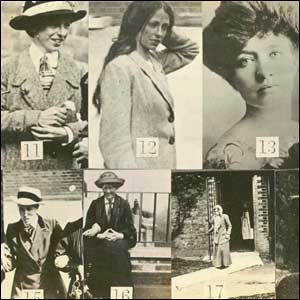

Even with their new equipment and surreptious methods, the police failed to adequately photograph each of the suffragettes. Look at picture 17, the one of Jennis Baines. She's standing too far away; you can't make out her face. Maybe the telephoto lens wasn't working that day? Compare 17 with picture 13, the (unexpected!) close-up of Kitty Marion. It's obviously not a surveillance photograph at all, but a personal portrait that the cops used in place of one. And look at picture 15, the one of "Miss Johansen." She's obviously struggling against the two police officers who have grabbed hold of her on both sides. The cop on her left (our right) has a set of keys dangling from his vest; perhaps they are leading her off to her new cell. The look on her face is full of tension and pain. There's a stark, almost violent contrast between it and the smile on Mary Richardson's face (picture 11, directly above picture 15) or Kitty Marion's thoughtful gaze (picture 13).

These brutal pictures bring us face to face with the stark reality of modern surveillance: a creation of the criminal justice system, not "democracy"; a reaction against effective protest; an instrument of political power; and a means by which to control both the bodies and images of "criminals." Despite what modern surveillance says about itself, there's never been a voluntary but "reluctant" acceptance of its presence. We, the inmates in the general prison, were never presented with a "difficult" but "regrettable" choice between liberty and security, there was no vote at all. Surveillance was simply, violently imposed upon us.

Nowhere is the violence of modern surveillance more evident than in the newly discovered photographs of one Evelyn Manesta. One of the window-smashers, Ms Manesta was also photographed surreptiously while in Holloway.

After her release from prison, Evelyn Manesta continued to engage in direct action. In March 1914, she and another suffragette named Lillian Forrester physically attacked paintings of classically "beautiful" women in the Manchester Art Museum, as a way of highlighting the hypocrisy of those who value paintings of beautiful women more than real live women (their example was Christabel Pankhurst, who was still in jail at the time). As part of the same action, at London's National Gallery, Mary Richardson (smiling picture 11 above) attacked Velasquez's Rokeby Venus.

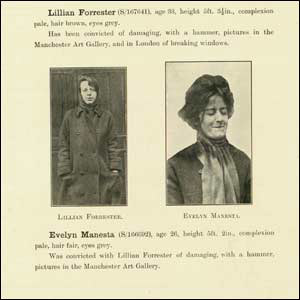

Shortly thereafter, the Home Office put out a "wanted" poster (reproduced below) for Forrester and Manesta, both of whom were convicted of various crimes in absentia. The caption at the top says: "Lillian Forrester (S/1676411), age 34, height, 5ft 5 1/2 inches, complexion pale, hair brown, eyes. grey. Has been convicted of damaging, with a hammer, pictures in the manchester Art Gallery, and in London of breaking windows." The caption at the bottom: "Evelyn Manesta (S/160001), age 26, height 5ft, 2 inches, complexion pale, hair fair, eyes grey. Was convicted with Lillian Forrester of damaging, with a hammer, pictures in the Manchester Art Gallery."

The picture of Forrester is pretty much what one expects to see: the subject, who doesn't realize she's being photographed from afar using a telephoto lens, is facing the camera and looking straight ahead; she's not making any facial expressions that hinder or prevent a genuine likeness from being recorded; and the viewer sees enough of the subject's body to get a sense of her height and weight. But the picture of Manesta is a real shocker: the subject seems fully aware she's being photographed, has her eyes closed, and is . . . smiling. She's also turned slightly away from the camera, and the cropping doesn't allow to viewer to see any of her body below the chest, which means there's no way to estimate her height or weight. In short, the picture is far more likley to result in a mistaken identification than a correct one. But it was used anyway, because the police just couldn't get one any better.

As it turns out, prior to publication, Evelyn Manesta's "wanted" picture had been both cropped and altered by the police's photography lab, which had been ordered to erase all traces of the extraordinary effort it had taken the police to "capture" the formidible Miss Manesta on film in the first place. Evidently, the telephoto lens just wasn't giving the police the type of pictures that they wanted, and so they had to take a photo of her "the old fashioned way," e.g., up-close and personal. Perhaps Evelyn Manesta wouldn't stand still; perhaps she kept moving to thwart the camera, which, she surely knew, required time and a motionless subject to take a good shot. And so the police had to assign a man to hold Evelyn Manesta in place. But he also had to remain out of sight; otherwise, he too would be photographed. And so, the cop dared to stand directly behind the suffragette, and use her body to shield him from the camera. Though she kept her hands in her pockets, Evelyn Manesta must have put up quite a fight, trying to escape his grasp. Moments before the photograph was taken, the "hidden" cop was forced to use his right arm to reach out and around, and pull her back by the throat, in towards him. In so doing, he not only exposed himself, but also the existence of the secret operation of which he was just a part. At that, Evelyn Manesta smiled. She'd beaten them.

Given the primitive technology they had to work with, the boys at the photo lab did a pretty good job. They managed to remove the cop -- not just his right arm, but also the fingers of his left hand and part of his head or hat -- from the picture and fill in the gaps that his removal created, especially around her neck. And so the police were able to restore what Evelyn Manesta's refusal to be photographed had disturbed: the asymmetrical power relations and clear distinctions between those who are visible (inmates) and those who are hidden (prison wardens and spies). But, to make the trick work, the boys at the lab had to hide their own traces, and so they "tightened" the picture by stretching it vertically. The effect makes Evelyn's face look thinner and thus older; she looks taller and thinner, even a bit like a young man. Her identity is escaping from the prison of the photograph. But where is it fleeing? The smile knows, but the mouth won't say.

-- Bill Brown, 23 October 2003.

By e-mail SCP@notbored.org

By snail mail: SCP c/o NOT BORED! POB 1115, Stuyvesant Station, New York City 10009-9998