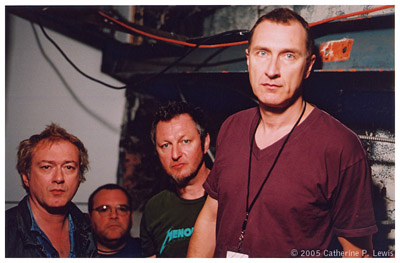

The original line-up of Gang of Four -- from left to right above: guitarist Andy Gill, drummer Hugo Burnham, bass guitarist Dave Allen and singer Jon King -- was together for four very productive years (1977 to 1981), during which the band released four albums (two of them great) and a handful of great EPs and singles. In May 1984, after the successive departures of Allen (formed the band Shriekback) and Burnham (went on to play with ABC, Nona Hendryx and Public Image Ltd.), Gang of Four broke up, a fact that wasn't widely announced, known nor lamented at the time.[1]

In 1990, EMI/Warner Bros. released A Brief History of the 20th Century, a padded-out compilation[2] that included songs from all four of the band's records, even Hard, its last and worst. But listeners weren't able to follow-up on what they'd heard: the original albums were out of print, and the band itself didn't have a recording contract. Polygram Records stepped in and convinced King and Gill to re-form the band and record new material. In 1991, with other musicians replacing Allen and Burnham, the Gang of Four released Mall and went out on tour to support it. In 1995, the band released Shrinkwrapped (Castle Records), onced again with other musicians replacing Allen and Burnham. To support the new record and the re-issue of Entertainment! by American Recordings/Infinite Zero, the band went out on tour once again.

I've seen Gang of Four perform three times: in 1981, at a small club in Ann Arbor, Michigan; in 1991, in Buffalo, New York, opening for Public Enemy; and in 1997, at the Limelight in New York City. At the Limelight, the band didn't play anything from Mall or Shrinkwrapped, which was unfortunate, because both were good albums. Instead, the band played nothing but its old material, and did so with a vehemence. It was exhilarating to listen to and experience: King and Gill weren't resorting to their "hits"; they were reclaiming them (from commercial oblivion), asserting them (the songs' continued richness and relevance), defending them (against dilution or plagiarism by other bands), and celebrating them (their existence in both the past and the present, which means in the future, too).

Ten years (!) after the release of Shrinkwrapped, a "new" Gang of Four record has been released. At first, Return the Gift (V2, 2005) appears to be yet another compilation of songs from 1977-1981 -- that is to say, a rip-off. Only 14 songs long, it is much shorter than either A Brief History, which included 20 songs, or 100 Flowers Bloom, a 40-song compilation released by Rhino/WEA in 1998. But Return the Gift is not a "new" compilation of old recordings: it's a collection of new recordings of old songs by the band's original line-up (King, Gill, Allen and Burnham).

Return the Gift is an extension of the remarkable project begun onstage in 1999 (the reclamation and celebration of the original recordings by the Gang of Four) into the recording studio. A project aiming to "return the gift"[3] -- the gift of those great old songs -- from the live stage (back) to the recording studio. But the new recordings are also an intensification of this project: return the gift from the middle-aged men who today play the songs (back) to the young men who wrote and recorded them more than 25 years ago. (There's a mumbling voice in the new "Anthrax" that speaks of the archaeology of trying to find out "who these people were.")

Of course, both recording studios and the original line-up of the Gang of Four have changed since 1981. There is no doubt -- it is an established or "natural" fact -- that recording technology has dramatically improved over the course of the last 25 years. But what of the particular members of the Gang of Four? Have they, too, "improved"? It's difficult to say: technological development is mostly a quantitative thing (how much, how fast), while artistic development is mostly if not exclusively qualitative (how good). The individual members of Gang of Four might well have become better musicians, but this would not necessarily mean that they'd become a better band. (The original Gang of Four was nothing if not a real band, whose music contained no "solos" or, if you prefer, nothing but solos by each of the players and thus the group itself. Furthermore, better individual musicianship, if taken to the extremes of laziness, self-indulgence or competitiveness, can sometimes distract from, diminish or even destroy the quality of the music being performed.)

And so Return the Gift is a very risky, if not impossible (doomed) adventure into largely unknown territory (who else in rock 'n' roll has done this?). To make the adventure a success, it isn't enough to be able to play -- to pick up and carry the weight of -- the old songs, which were in many cases quite "heavy" (I mean emotionally charged: the guilty pleasures of the final heedless rush in "Damaged Goods," the confused confidence in "Natural's Not In It," the terror and dread in "He'd Send in the Army," the sense of displacement and "flatness" in "We Live As We Dream, Alone," et al.). No, to make this work the band must play their old songs better than they were originally played. But is it in fact possible to play these songs any better than they were originally played? It may not be. And so it is precisely the merit of this unique collection that it even attempts to try, that is to say, tries to do the impossible.

By and large, Return the Gift lives up to its impossible ambitions. The song selection is pretty good: to have been even better, Return the Gift would have replaced "Capital" (musically uninteresting) and "What We All Want" (it's been re-recorded before) with "5.45," "It's Her Factory," "Cheeseburger," "Outside the trains don't run on time," and/or even the apparently forgotten classic "Armalite Rifle." Only one song is an embarassing failure. Unfortunately that one song ("We Live As We Dream, Alone," from Songs of the Free) is one of the band's very best (and least known) songs. Its new version lacks the very thing that made the original version so great, and that is used to enrich and re-energize the new versions of "Why Theory?" "Anthrax" and "He'd Send in the Army": Andy Gill's flat, matter-of-fact, baritone speaking-voice. In its place, Gill sings the words in a wavering tenor and ends up sounding like a bad imitation of Iggy Pop imitating David Bowie. The other bad news (not as bad but almost) is that the new versions of "Ether" and "Damaged Goods," which are also among the band's very best songs, aren't as good as the original versions: the former lacks the original's anguish and dread, and the latter lacks the original's drive, especially at the end, when it counts.

I reckon that the new version of "To Hell with Poverty" is just as good as the original version, which means it's pretty damn good (it was never among my favorites). But it's a great song with which to begin Return the Gift. "In this land right now / Some are insane and they are in charge" -- this was true in 1981, the first year of Ronald Reagan's terrifying reign, and it still is true today, at the height of George W. Bush's murderous reign. As a matter of fact, some of the same lunatics (Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfield) are still in charge! Similar moments of shocking recognition -- it's still 1981! -- occur in "Anthrax," "He'd Send in the Army," "I Love a Man in Uniform," and especially "Ether" ("to get to the root of the problem/fly the flag on foreign soil," "There may be oil," and "each day more deaths").

Now for the good news: more than half of the 14 new performances are better than the original versions. In "Anthrax," "Natural's Not In It," "Not Great Men," "Anthrax," "He'd Send in the Army" and "At Home He's a Tourist," Andy Gill's fire-breathing guitar parts are brighter, and Allen & Burnham's rhythms and shifts are more physical, more muscular, than they ever were. In the new, definitive versions of "Paralyzed," "Natural's Not In It," "He'd Send in the Army," "Why Theory?" "At Home He's A Tourist," and "I Love a Man in Uniform," the vocals -- the singing voices and the speaking voices, what they are saying and the tones they are taking in their various back-and-forth exchanges -- are much better projected and recorded, and thus are easier to hear, follow and understand.

But the most improved, and thus the most noteworthy song on Return the Gift -- a kind of compensation for the destruction of "We Live As We Dream, Alone" -- is "I Love a Man in Uniform." Originally released on Songs of the Free (1982), "I Love a Man in Uniform" was a minor hit on dance-floors and college radio stations. I never liked the song, despite its clear mockery of the militarism of Thatcher and Reagan, and I was somewhat embarassed by its modest success. The "groove" laid down by drummer Hugo Burnham and new bassist Sara Lee was stiff, the guitar playing was domesticated, and Sara's background vocals were weak, which completely undermined the song's gimmick: the woman's mocking exclamation, "Oh, man, you must be joking."

In the new version, there's no gimmick. Perhaps there doesn't need to be when you've got Dave Allen on bass guitar instead of Sara Lee: the rhythm section is so strong and self-confident that Andy Gill can play his guitar freely and thus give the song space to come to life. When the narrator, a determined and confused little prick ("to have ambition was my ambition"), says that his "woman" needed "protection" and that's why he joined the armed forces, or when he boasts that the time he spent with his girl was time well-spent, it isn't a woman's voice who says "Oh, man you must be joking," but a man's.

Time has gone by. The little prick isn't boasting that he's just enlisted, his woman wisecracking at his side, his buddies laughing at him. He's already enlisted, and he's now in basic training or actually in combat. When he swaggers and makes his ridiculous boasts, the wisecrack comes from one of his buddies, not in a girly falsetto, but in a "straight" male voice. His woman, all of the women, are back at home. There's no reason to pretend that what she says matters. There's no irony, either. When "Oh, man you must be joking" is first thrown at him, he starts saying, a little too soon, "She needed to be protected," as if there's no time for jokes. There's no time for punchlines. Orders have been requested, orders have been given, shots have been fired. No casualties reported as yet.

-- Bill NOT BORED! 6 December 2005[1] See our Gang of Four Surrender, published in NOT BORED! #3, May 1984.

[2] The compilation's liner notes were written by Greil Marcus, who'd first written about the Gang of Four in New West in 1979. His 1990 liner notes -- reprinted in In the Fascist Bathroom: Punk in Pop Music, 1977-1992 -- are easily the best essay ever written about the band's music.

The Gang of Four acted out, and out into records, a picture of an individual who had discovered that ordinary life -- the gestures of affection and resentment one made every day, the catchphrases one spoke every day as if one had invented them -- is in fact sold and bought as grease for shopping and silence, for the accumulation of capital and passivity. The person who has made this remarkable discovery begins to re-examine his or her life, and it begins to look different: 'Natural's Not In It.' History -- 'Not Great Men.' A woman in the home: 'It's Her factory.'

Life looks different, but it doesn't change. The Gang of Four pursued their subject's discoveries not as if they might lead to some grand general strike [...] but as if, once recognized, those discoveries would remain trapped in the prison of familiarity. Playing everyman on stage, Jon King was never free. He was an explosion of doubt. He dramatized a glimpse of liberation, but simultaneously the wish the conform, to be at home in the only home available, no matter how false.

[...] The Gang of Four offerred no anthems, no tunes of right and wrong. They were interested in constructing a drama in which each listener found his or her place as a new historical subject, set free from all certainties, all forms of common sense and obvious conclusions, set free in a convulsion you can hear in so many of the numbers on this disc, perhaps most fiercely in 'Return the Gift.'

Though there were no anthems, there was a theme, and that theme was the military or, if you prefer, the militarization of society. "Armalite Rifle," "Anthrax," "Guns Before Butter," "Outside the Trains Don't Run on Time," "He'd Send in the Army," "I Love a Man in Uniform" -- here the individual pictured by the Gang of Four is active in two different social worlds: the ordinary life of civilians (workers, housewifes, consumers), or the ordinary life of soldiers. This theme is dramatized in the music itself, in the Gang of Four "sound," no matter what the lyrics are about, in its martial tone, its discipline, precision and rigid postures. On stage, the musician who acted out the soldier's discoveries wasn't Jon King, but Andy Gill. He, too, was never free. But, in contrast to King (the disabused corporate executive), Gill acted like a prisoner of war forced to sing and play his guitar at the point of a gun. He dramatized a glimpse of confinement, but also the wish to escape, to be somewhere, anywhere else.

[3] The phrase "Return the Gift" comes from the title of a great song from Entertainment! (Greil Marcus: "Return the gift, the song is shouting; give it back before it's too late!") But this song does not appear on Return the Gift, the album that bears its name. The phrase stirs many associations, among them potlatch, which, among certain tribes of Native Americans, is a form of competition, conquest or social control in which spectacular self-sacrifices are "exchanged" as gifts. Potlatch was the title of the journal published by the Lettrist International between 1954 and 1957.