Most art critics (those who write about art in exchange for money) would probably designate the photographs made by Miroslav Tich as outsider art. That is to say, Tich a self-taught Czech photographer who used homemade cameras and lenses to take surreptitious shots of young women and girls was outside of society and thus a creep, someone with whom we those inside would not want to socialize or be associated, but who attracts and holds our intellectual interest because of the unexpected beauty of his photographs. Who would have thought that such an ugly person could make such beautiful art?

But in this society, this global society that includes both small villages in Central Europe as well as large cities in America and Western Europe, there are no insiders, and so there cannot be any outsiders, either. Everyone is deprived of a truly social existence by an organization that is only a vast assembly of markets and centers of production and consumption; everyone is alienated, isolated and separated off from everyone else. The only difference is that some people have the material means that allow them to accept, tolerate and become acclimated to such asocial conditions, while the rest do not and suffer accordingly (that is to say, doubly).

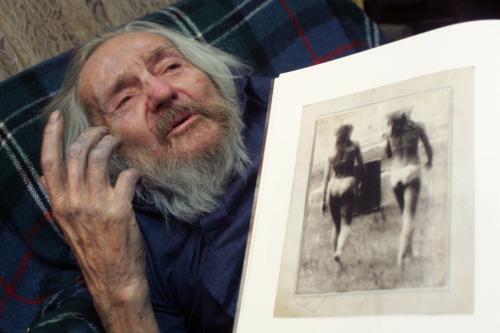

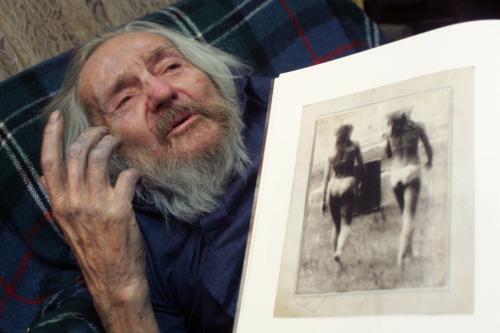

Given these facts, it would be better to say that Miroslav Tich is distant from us. Born in 1926, he lived in Kyjov, a small village in the country once known as Czechoslovakia. He was poor or, at least, he did not work in the established sense of the word. He did not sell his photographs to make a living, nor did he even exhibit them. Indeed, he rarely made more than one print of each shot he took. (Later, when he became somewhat famous, he didnt attend the exhibitions of his photographs, even when they were held in Brno, just a few miles from where he lived.) He was not part of any institution: no church, political party or community organization could claim him as a member. He never married and never had any children. He didnt follow the news or the latest developments in the world of art.

It seems that Tich spent all of his time at least during a certain period of his life by constructing cameras and lenses out of rudimentary materials, going out for meandering walks, hiding in the bushes or behind fences at playgrounds, swimming pools and public streets, watching the women and girls whom he happened to find along his way, taking black-and-white photographs of them, developing those photos in his homemade studio, framing the intentionally defective prints in homemade pasteboard mounts, decorating those mounts, drinking rum, and, no doubt, engaging in reveries, fantasies and daydreams.

But Tich was a self-conscious artist, not an idiot savant. In his youth, he studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. After 1948, when the Communist Party seized control of Czechoslovakia, students such as Tich were required to paint in the Social Realist style. Instead of doing so, Tich dropped out of the Academy. He was punished by being drafted into the military, where, it appears, he was either injured or declared mentally unfit (upon his return to Kyjov, he was awarded a small disability pension).

In the 1950s, Tich returned to painting; once again, he refused to paint in the Social Realist style, choosing instead to follow modernism and his own inspiration. Because he didnt do what was obligatory and engaged in what was forbidden, the bureaucrats of the Communist Party considered him to be a dissident (although he was never a part of any organized political movement), kept him under constant surveillance and, it appears, even institutionalized him at times that the Party wanted to maintain a good appearance (May Day, et. al).

In the 1960s perhaps in response to the changes in European culture brought about by the students movement, the counter-culture and revolutionary groups such as the Situationist International Tich decided to look like the creep that the authorities considered him to be. He stopped shaving and cutting his hair, and began wearing the same suit every day. He also switched from painting to photography, which he pursued obsessively until the 1980s, when he once again returned to painting and drawing.

Significantly, nothing really changed for him after 1989, despite the Velvet Revolution. Solitary as always, he remained distant or, rather, kept his distance from everyone and everything, but especially from the worlds of art and commerce.

Perhaps Tich lived to such a ripe old age (he died in 2011) because he was always surprised: surprised to find such beauty in the ordinary women in his village; surprised by the power of his own responses to that beauty; and surprised that, even after years and years of engaging in his obsessive-compulsive behavior, he still found beautiful women (and/or still found women beautiful) and his responses to their beauty remained strong.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Tichs voyeuristic photographs have a powerful erotic charge. Perfectly ordinary people, not stars or members of the ruling class (Stalinist bureaucrats or bourgeois businesswomen), the women and girls he photographed generally did not know that he was taking their picture, and he often focused upon their curvy tits and asses. And when they did realize that Tich was out there, photographing them, they were surprised, reproachful or undecided about what to do. Some werent even sure that his camera was actually a real, functioning device, and so struck poses for him. In any event, Tich managed to photograph those reactions, and thus captured the complex interplay of watcher and watched.

It would be wrong to say that Tichs photographs are pornographic images, even though he no doubt looked at them while masturbating. Pornography, that is to say, commercial pornography the specialized, spectacular product of a truly immense and ever-growing industry never produces surprise, nor does it leave anything to the imagination. These are not the things that its consumers want or, at the very least, they are not what its producers think that the consumers of pornography want. These consumers want to see everything, up-close and clearly, with virtually clinical precision; and they want see every act brought to its proper conclusion (cum being ejaculated into or onto a womans body, which has long been known by the obviously capitalist phrase the money shot).

By contrast, Tichs photographs are blurry and vague, so much so that he sometimes felt compelled to use a pencil to highlight the outlines of the women and girls he desired but could not have. No: his photographs arent examples of pornography, but obvious instances of erotic art, and this is why they surprise us. They engage our imaginations, not our brains (what we think, what we know, and what we think we know).

In short, Tichs photographs collapse distance: not only the distance that separates us from him, but the distance that separates us from ourselves. Despite the limited means that he used to produce them, and his equally limited subject matter, these photographs that is, if we allow ourselves to experience them, rather than merely see them fill us with excitement, warmth, surprise and the conviction that what we are experiencing is true, not false or faked. We are certainly seeing the truth about Tich himself.

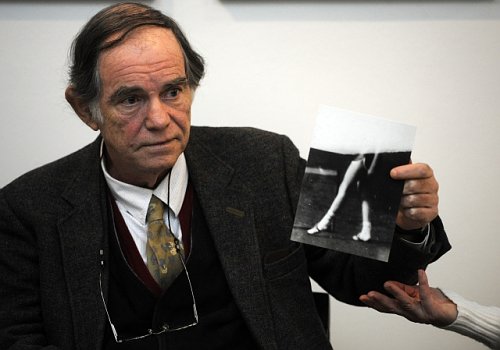

As Gianfranco Sanguinetti says in his introduction to Miroslav Tich: Forms of Truth (Kant, 2011), I am not an art critic fortunately, perhaps, for the reader, and most definitely for me. As a matter of fact, Sanguinetti is a former member of the Situationist International, a writer of scandalous texts about Italy in the 1970s, and, it would seem, an amateur (that is to say, casual) art collector. I love this art, he says about Tichs photographs, which I have long collected for my personal pleasure. He has also come to know and like Miroslav Tich well that is, personally and wrote his introduction, as well as shared with the world his extensive collection of Tichs photographs, simply () to repay the debt of acquaintance with the man and his art. Significantly, perhaps, he repaid this debt while Tich was still alive; the photographer died shortly after Forms of Truth was published.

Sanguinettis introduction, like all of his texts, is full of rich and pertinent references to and quotations from a wide variety of sources: poets (Giacomo Leopardi), art critics (Edgar Wind), critical theorists (Walter Benjamin), painters (Kandinsky), and novelists (Stendahl). A native speaker of Italian, he also knows English, Czech, and French (which is the language in which the original text was written and then translated into English by Richard Drury). As a result, his introduction, like all of his writings, is a very stimulating read.

But Sanguinettis introduction to Forms of Truth is not a work of criticism or theoretical exegesis. It is divided into nineteen numbered sections, each of which ends with a conclusion that has been reached. These conclusions are similar in form: each one begins with some variation on In this lies, This is why, or This is the, and includes a reference to Tich himself or his work, which is described by or given the following attributes: strength, beauty, universality, refinement, rigor, defiant challenge, modernity, classic, scandalous, aura, originality, eloquence, painted, erotic art, poetic art, freedom, excellence and strength.

Prompted by Sanguinettis comments about poetry or, rather, about the absence of poetry from the general art market and most of the other arts we can say that his introduction is a kind of prose poem, but a unique and original one. After a while, it begins to sing in our ears.