"If it's a good riff, people are going to listen to it," even in a commercial, said Jason Fine, senior editor at Rolling Stone magazine. "It doesn't particularly bother me or steal the song's meaning from me. I know a lot of people do feel that way, but that's become an outdated way of thinking." -- New York Times, 6 November 2002.

As far as I know, this shit started in 1986, when Michael Jackson allowed the Nike Corporation to abuse the Beatles' song "Revolution" in one of its TV commercials. I'm sure that plenty of great rock 'n' roll songs had been licensed for commercial use before 1986, but Nike's use of "Revolution" was a watershed event, and not only because its composer, John Lennon, had died six years previously and no doubt would have been violently opposed to the idea had he been alive to hear it. (Neither Paul McCartney nor Yoko Ono were able to do anything to stop Jackson, because he'd successfully outbid them both to acquire the rights to all of the Beatles' songs.) The commercialization of "Revolution" was a watershed event because the song itself was so obviously ill-suited for use in a commercial.

Written in 1968 and only released as a single, "Revolution" was a serious, impassioned and controversial discussion of the dangers of social revolution, which was a very real prospect at the time. Unsatisfied with the way the (apparently) anti-revolutionary song was originally received, Lennon later re-recorded it for the so-called The White Album as "Revolution #1," which changed the guarded "no" of the original ("don't you know you can count me out") to a furtive "yes" ("count me in"). The White Album also included Lennon's "Revolution #9," which was a 9-minute-long collage of tape recordings in the style of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and not a proper "song." Lennon's point in recording three totally different "Revolutions" in a single year was clear: social revolution can't be treated lightly, definitively or with impunity, for it is both unpredictable and certain to spin "back" and overthrow the position of everyone, even or especially that of the revolutionary.

But the people at Nike, the staff at its advertising agency and Michael Jackson all thought that the Beatles' "Revolution" (the first one) would make a great element in a "revolutionary" TV commercial for a "revolutionary" product. No doubt they thought or managed to convince themselves that they weren't prostituting or raping the song by using it to sell something as banal as sneakers, but that they were in fact cleverly "adapting" the song to changed circumstances and were thus showing it the highest form of respect. Unfortunately for these dialecticians, the subtleties of Nike's "Revolution" commercial were lost on millions of Beatle fans, who were virtually unanimous in their hatred of it. Stung by the experience, Michael Jackson has in the years since then been very conservative in his decisions concerning the commercial exploitation of the Beatles' songbook. One also notes that the use of well-known rock 'n' roll songs in TV commercials -- though a constant feature of the last 15 years -- has come in waves, with lulls or breaks in between, as if the advertisers and/or the songs' copyright owners are quite aware that consumers will only tolerate so much commercialization of the music they love before they rebel or at least stop buying the products that use rock music in their advertising campaigns.

And yet the fucking things won't go away. Just when you think that you've seen it all -- the Rolling Stones's "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" used to sell "Snickers" candy bars, Lou Reed astride a Honda motorbike, and William S. Burroughs as a salesman for Nike -- you turn on the TV and come upon a fresh butchery so gruesome that you wouldn't have thought it possible: Bob Marley's "Get Up, Stand Up" used to sell Timberland boots; the Buzzcocks's "What do I get?" used to sell cars (the Buzzcocks?!); not one but two songs from The Who's Who's Next ("Baba O'Riley" and "Bargain") used to sell cars; David Bowie's "Changes" used to publicize Microsoft; Iggy Pop's "Lust for Life" used to sell Heineken beer; Devo's "It's a Beautiful World" used to celebrate Target's superstores and "Whip It" used to sell Pringles potato chips (yes, I saw it, it really aired!); Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Fortunate Son" (no longer owned by its author, John Fogerty) used to sell Wrangler jeans to flag-waving Americans, etc. etc.

Don't these marketing and advertising people listen to the words of these songs, most of which concern serious issues, not banalities? Don't they realize that the words are all-too-frequently saying the exact opposite of what the commercial is saying? They must realize, because on several occasions they have been careful to remove a key word or even an entire line: "Don't want to be a richer man" dropped from Bowie's "Changes"; "It ain't me, I ain't no senator's son" excised from CCR's "Fortunate Son"; "It's a beautiful world for you, not me" removed from Devo's "Beautiful World," etc. etc. These aren't "bloodless" cuts; on the contrary, they tear into these songs' very hearts. Without their ironic or confrontational lines, which almost always form their respective centers, these songs are either corpses or cripples. Blasted out of the TV set every 10 minutes, dead or alive, they invite us to join the dance macabre.

What about the musicians themselves? Not all of them are dead. Some of them even own the rights to their songs! Why aren't they hiring lawyers and suing? Why are they allowing their songs to be butchered? The obvious answer is "money." If you are Devo or the Buzzcocks, both of whom broke up in the 1980s, or Credence Clearwater Revival, who broke up in the 1970s, these deals may be the only way they are going to make any money at all from your back catalogue of recordings. If you are Lou Reed or Iggy Pop, both of whom are still active recording artists but have never had (and aren't ever likely to have) a #1 hit single, these deals may be the only way you are ever going to make any "serious money" in show business. And so these musicians probably figure, "Might as well get it now while I still can. Everyone else is." But money or, rather, greed cannot account for all of what's going on. There must be other factors at work as well. What Michael Jackson did to "Revolution" 15 years ago, today people are doing to their own songs!

It'll help if we focus on a couple of examples. Take David Bowie: it doesn't surprise me that he's acting like a greedy, cynical bastard these days. ("Use the cover of Alladin Sane to sell Absolut vodka?! Turn "Watch That Man" into an ad for The Gap?! Sure! Where do I sign?") It was obvious that Bowie was never attached or committed to the various personae, singing styles, lyrical concerns and musical forms that he'd pick up, use for a while and then dispose of. It was all a put-on for him. And so there's no sting, no resentment, no anger, when Bowie sells anything he's got to whomever wants to buy it (as long as the price is right).

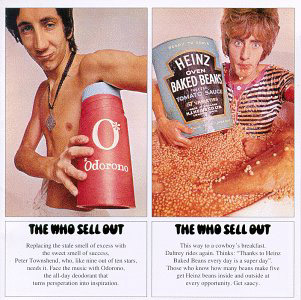

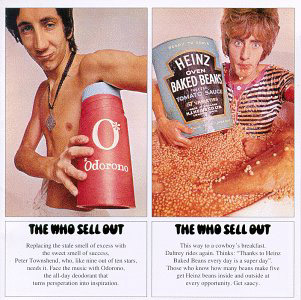

But Pete Townshend's zeal for commercializing his songs is a real shock. His music didn't change from album to album. As he stated in "Long Live Rock," a single from 1973, he was going to continue to play loud, hard rock'n'roll, even if others claimed that "rock is dead." (Indeed, it wasn't until 1978 and the advent of punk that he finally wrote a song that admitted "The Music Must Change.") Townshend's commitment to "the music" was strong and fast, and it inspired a great many people, David Bowie among them.

Townshend's probably got quite a lot of money from his days with the Who. Maybe he needs a little extra money now and again. Or maybe he isn't rich after all and needs more money than we might think. In any event, because he is Pete Townshend (i.e., a man with a well-deserved and long-standing reputation for hard work, honesty and sticking to his guns), you'd think that he'd be cool about it if he ever needed to resort to selling his songs to advertisers. Unlike Bowie, he wouldn't sell any of the songs that he knew or imagined to be dear to his millions of fans, and he wouldn't allow any of the songs that he sold to be trivialized or butchered. But Townshend hasn't been cool about selling out. In fact, he's been quite a dick about it.

Townshend allowed "Baba O'Riley" to be turned into a commercial for a sports utility vehicle! (It's still hard to get used to.). The opening track on 1971's Who's Next, "Baba O'Riley" used to be a very serious song that denounced the Woodstock concert as a "teenage wasteland," paid musical tribute to an avant-garde composer (Terry Riley), and based the chords of its glittering synthesizer part (B alternating with A) on the holy name of Baba (as in Mehr Baba, Townshend's spiritual guide at the time). To make matters worse, Townshend allowed two songs on Who's Next -- "Baba O'Riley" and "Bargain," the song that immediately follows "Baba" on Side One -- to be turned into car commercials. (Good God! Is "Going Mobile" next, that is, once the troublesome line "I don't care about pollution" has been removed?) Finally, Townshend allowed "Bargain" -- a fierce song about a man absolutely desperate for the love of a woman -- to be butchered in a uniquely horrible fashion.

The conceit of this spot for Nissan Xterra is that the voice-over announcer answers the singer as if the two were engaged in a conversation. But the announcer doesn't agree with the singer, as you might expect (it's a well-known song by a very popular band, after all). Instead, the announcer flatly contradicts what the singer is saying. "I'd pay any price just to have you," the singer says, only to be told by the announcer "You don't have to pay any price." By the end of this weird debate, the announcer has utterly trounced the singer, of course (after all, this is a commercial for the great "bargains" you can get at your local Nissan dealer). But the singer's defeat is a very strange thing to have happen in a commercial that is apparently based upon the premise that people have good feelings (and not scorn or ridicule) for the Who's music and so will buy something associated with it.

And so, maybe I was wrong about Townshend: maybe he isn't the man I thought he was. Maybe he's always been a greedy, cynical bastard. Or maybe he's changed and has only recently become a greedy, cynical bastard. But neither greed nor cynicism (nor bastardy) fully explains how someone could sign off on and profit from atrocities such as the "Baba O'Riley" and "Bargain" TV spots. Both common sense and personal experience indicate that only someone who hates himself and consequently has no respect whatsoever for the value or quality of the songs he's written -- only a musician who has nothing but contempt or hostility for his fans and admirers -- could do such things. "Fuck! Why should anyone else care about what happens to these songs if I don't care?" Townshend might well have said to himself when he signed the contracts. "After all, I'm the one who wrote them, aren't I? And if I say 'Baba O'Riley' is a piece of shit, then it's a piece of shit, end of story."

If Townshend did indeed say something like this to himself, then we propose the following should be his obituary: Pete Townshend, who proclaimed "Hope I die before I get old" when he started out as a young man, got his wish, but with a twist: he did indeed die before he got old, but didn't realize it and continued to go about his business as if nothing had happened.

--Bill Not Bored, 10 December 2001.

21 November 2002: since this essay was written, Townshend has licensed the use of the theme from the 1969 Who album Tommy for use in a TV commercial for Claritin, an allergy medicine; the 1979 Who song "Who Are You? for use by TNN, a cable TV station; and the 1982 solo-album hit "Let my Love Open the Door" for use by NBC-TV.

13 September 2003: Townshend has licensed the 1966 Who song "Happy Jack" for use in a TV commercial for Hummer, a truck invented by the US military and now sold commercially.

17 November 2003: Townshend has licensed the classic 1971 song "Won't Get Fooled Again" for use in a TV commercial for MSNBC news program Hardball with Chris Matthews.

18 July 2004: Townshend refuses to let Michael Moore use "Won't Get Fooled Again" in "Fahrenheit 911."

20 April 2005: in the last few months, Townshend has licensed "I Can't Explain" (1965) to the PGA Tour/ABC Sports, "I Can See For Miles" (1965) to Silverstar Headlights, "Pinball Wizard" (1969) to Saab, "Going Mobile" (1971) to CBS-TV in New York City, "Who are you?" to CSI: Las Vegas, and "Let My Love Open the Door" (1982) to JC Penny.

8 September 2008: Townshend has licensed "Join Together" (1972) to Nissan.

19 January 2009: Townshend has licensed "My Generation" (1965) to Pepsi.