It's the very first thing you notice about Dennis Rodman's remarkable autobiography Bad As I Wanna Be, published by Delacorte in June 1996 so as to coincide with the NBA Finals.

The typography is "gimmicky." Over and over again, for the entire length of the text, the reader is confronted with whole sentences printed in different fonts, in larger point sizes, in boldface or italics (or boldface and italics) and/or in full capitals. Occasionally, single words or phrases are printed, shall we say, differently from the norm.

THAT'S JUST IT,

of course: Dennis Rodman is different from the norm. He's an "in-your- face" basketball player, and his autobiography is an "in-your-face" book.

Get it?

But there's quite a bit more to "get" in Bad As I Wanna Be -- to be precise, there's more being communicated by the "gimmicky" typography -- than one might expect from a poorly-organized, all-too-short and irritatingly sketchy book that was clearly designed to

CASH IN

on Rodman's spectacular success as a member of the revitalized Chicago Bulls basketball team. Masquerading as a gimmick,

the jumpy typography is a metaphor

for Dennis's multi-colored hair, which is itself a metaphor for his sexual persona, which is itself a super-metaphor for the completeness of Dennis's refusal to be denied participation in the totality of what it means to be a human being. In a word, the typography is a metaphor for his total and therefore exemplary refusal to remain domesticated, despite all the pressures he is under to stay as he has been or to become what he "should" be.

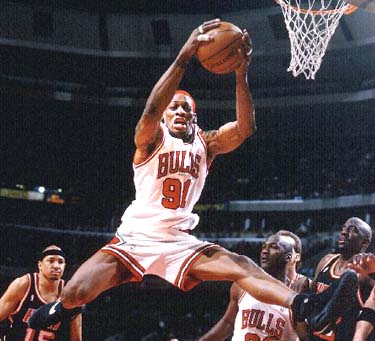

An "animal" on the basketball court, Dennis Rodman is nevertheless the most human basketball star ever to play the game.

This makes him a spectacle only to the extent that the other players, who generally pride themselves on being picture-perfect "role models," do not seem to be human beings at all.

As has been noted elsewhere, it is Rodman's ceaselessly inventive performance of his "de-domestication" that makes him so, er, ah -- sorry to use a word that even seems silly when it is uttered by "revolutionaries" -- revolutionary. His much-vaunted "negativity" has created untold numbers of new radical possibilities and expectations for all kinds of people. Thanks to Rodman, some of America's most fixed and therefore oppressive images -- of what it means to be a star professional athlete, a physically powerful male human, and a black male athlete -- have been loosened and set adrift. If only critical theorists and professional "revolutionaries" could be as wild and distracting as Dennis Rodman is!

But, alas, this is rarely the case.

Take for example the collection of essays written in the 1970s by the French communist Jacques Camatte and published in translation by Autonomedia in 1995 under the title This World We Must Leave and Other Essays. "Until now," Camatte announces in the title essay, "all sides have argued as if human beings [have] remained unchanged in different class societies and under the domination of capital." Supposedly striking out into completely new and unknown territory, brave Camatte claims that the widely observed "autonomization" and becoming-human of capital have been accompanied -- indeed, made possible -- by the capitalization or "domestication" of people living in advanced capitalist societies. This double movement of autonomization and domestication, Camatte writes, is ultimately responsible for "the return to 'barbarism,' as analyzed by R. Luxemburg and the entire left wing of the Frankfurt School; the destruction of the human species, as is evident to each and all today; finally, a state of stagnation in which the capitalist mode of production survives by adapting itself to a degenerated humanity which lacks the power to destroy it."

Let us leave aside the question of the becoming-human of capital -- it has been adequately treated in our discussions of the situationists' critique of "the society of the spectacle" -- and ask

what, precisely, is domestication?

In a 1980 text entitled "Echoes of the Past," Camatte explains that "the scientific presuppositions established in the neolithic with the spread of animal husbandry went hand in hand with the development toward [human] domestication [...] And it shows up again in this vital contradiction: men always want to distinguish themselves from beasts [of burden], yet they constantly treat each other like animals." Forget about the way veal is produced:

we are the veal.

"The result of . . . technological process has been that, not only animals, but also humans themselves have been domesticated and adapted to the needs of industrial society," says Chris Korda, founder of the Church of Euthanasia and member of

, no doubt unaware of Jacques Camatte's "bold" work in this area. When it comes to watching the spectacle of "laboratory" animals being used in so-called scientific research, Korda says, "we can see that's cruel, we can see that those animals are suffering, it's essentially 'inhumane.' What a curious use of the word, because what we are not able to see is that our lives have been equally affected, and that humans have also suffered at the hands of industrial society."

DOMESTICATED HUMANS

-- people who have been successfully conditioned by the inhumane capitalist mode of production to "have a tendency to see themselves as a herd that they have to make prosper and grow" -- have been dispossessed of the faculties of "action, language, rhythm, and imagination," Camatte says. In

the society of the spectacle

-- Camatte's metaphor is "the community of capital" -- "there are no longer classes, only generalized slavery, accompanied by massification and homogenization of human beings and products." There is now only one element relating the "reduced" or domesticated human being to the external world:

SEXUALITY,

"which," Camatte awkwardly explains, "fills the void of the senses." Sexuality seems to make Jacques Camatte uncomfortable. For him, "pansexuality, or more exactly the pansexualization of being that Freud interpreted as an invariant characteristic of human beings," is in reality "the result of [human beings'] mutilation" at the hands of capital.

One look at Dennis Rodman tells us that Freud was

RIGHT

and Camatte is

WRONG.

The fuel for Rodman's intense and continuously-growing popularity clearly comes from the flamboyantly liberated and polymorphous perverse sexuality that he has -- in the very process of healing his "mutilation" -- discovered in himself.

As Rodman says in his book, he'd be just another nigger without basketball, but he'd be just another black basketball player without sexuality.

It should come as absolutely no surprise that Dennis -- like his ex-lover Madonna, who is perhaps the only American performance artist who is at his level of skill -- is pansexual. Dennis Rodman -- easily one of the strongest, most physically aggressive and intimidating players in the history of the NBA -- sleeps with women, fantasizes about men, dresses in drag, and publicly supports gays and lesbians. De-domestication, which is, in Dennis's words, doing things that "make me feel like a total person and not just a one-dimensional man," is a profoundly sexual experience. De-domestication is allowing "your body to go and explore anything it wants."

It is the revolution of bodily life, bro.

The author on tour to support Bad As I Wanna Be, 1996

The author on tour to support Bad As I Wanna Be, 1996

Where Dennis Rodman eclipses Madonna -- indeed, where Dennis Rodman eclipses just about everyone these days, but especially the specialists in revolution -- is in his awareness that his sexually-charged efforts to become a fully de-domesticated man is an instance of

class struggle.

Nothing but a mere worker (a salaried slave) in the eyes of some of his coaches and all of the economic powers behind the NBA, Dennis Rodman refuses to be reduced to a thing, to a commodity, to a quantity of labor power to be bought and sold. And this refusal isn't so much a matter of money as it is a matter of working conditions at the point of production, so to speak. "The bottom line is, this league wants to control its players," Rodman writes. "They want to restrict players from doing things that are natural and human to do. They don't want anybody insulting the people who buy the tickets -- the wealthy corporate types, because they're the only ones who can afford to go anymore." More than that, the NBA doesn't want players thinking and acting for themselves while they are on the court, even if it means that good teams lose important basketball games. In this regard,

the NBA is just like every other capitalist enterprise, whether it is privately or bureaucratically owned.

Towards the end of his book -- in a story that might easily be overlooked, for it concerns the mechanics of the game of basketball -- Rodman recalls the playoffs in which the San Antonio Spurs (Rodman's putative "owners" and "managers" at the time) played the defending champion Houston Rockets. "We lost the first two games -- at home, even -- because the defense we were running was ridiculous," Rodman writes. "Do you want to know who changed the defense for the next two games, after we got to Houston? I did. I saw what we were doing wrong, and I set out to change it. I finally got [Spurs' coach] Bob Hill to see it my way, and it worked. David [Robinson] played Hakeem [Olajuwon] straight up. Hakeem got what he was going to get anyway, but we stopped everyone else. That's the whole key to stopping [the Rockets]: give Hakeem what he wants and clamp down on everybody else.

It's not that hard to figure out."

Shortly after this series, which the Spurs lost to the Rockets, the Spurs traded Rodman to the Chicago Bulls for next to nothing.

What pansexualist and typographical artist Dennis Rodman has got in his multi-colored head is socialist basketball, a basketball team that is managed and coached by its own members. Who knows better how to do something than the people who can actually get it done? Bob Hill and the San Antonio Spurs' organization couldn't tolerate even the semblance of such a team, so they got rid of Rodman and have been a third-rate team ever since. But Chuck Daly and the Detroit Pistons and Phil Jackson and the Chicago Bulls know the value of socialist production (perhaps precisely because they themselves are employed by enterprises based in the industrial Midwest), and so have made a home for

the greatest rebounder and all-around defensive player the NBA has ever seen.

After all, it is in the industrial Midwest that the working classes -- the producers of automobile pistons and the crews of the slaughterhouses -- have known for generations that there is a profound discontinuity between the way a productive enterprise is supposed to function and the way it actually does function, and that, if attempted according to management's organizational plan and nothing else,

the enterprise will not run at all.

It is in the factories of the industrial Midwest that socialism is actually at work, for it is in these factories that collectivities of workers are allowed to band together and manage at least some of their own work, precisely because it is the only way their bosses can get the job done and make some money. The connection between Dennis Rodman's de-domestication and the on-going struggle in America to propagate and move closer towards socialism is so obvious it just jumps out at you.

But can you catch the rebound, bro?

[AUDIO RECORDINGS] [BACK ISSUES] [HOME] [LINKS] [SCANNER ABUSE] [SELECTED TEXTS] [TRANSLATIONS]

[LETTRIST INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVE] [SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVE]

To Contact Us:

Info@notbored.org

ISSN 1084-7340.

Snail mail: POB 1115, Stuyvesant Station, New York City 10009-9998